In this module you have learned about two widely used experiment paradigms in sentence comprehension: the garden path paradigm, and the filled gap paradigm.

For this discussion topic, I would like you to learn about, and introduce to the class, another useful paradigm: the agreement attraction paradigm.

An easy way to understand agreement attraction is with an example. Compare the following sentences:

-

- The key is on the table.

- The key are on the table.

-

- The key to the language lab is on the table.

- The key to the language labs are on the table.

Sentence 1b is ungrammatical: the plural verb are does not match the singular subject key. Sentence 2b is also ungrammatical for the same reason, but people often don't notice the grammar

error, because they're distracted by the plural noun "language labs" before the verb, even though this noun is not actually the subject. This is an example of agreement attraction: even though the verb

are is supposed to agree with key, the person reading the sentence might get "attracted" by another nearby noun (language labs) and and think the verb agrees with that

other noun.

Even if people consciously notice the error (e.g., even if people are able to correctly say "sentence 2b has a grammatical error"), they might not process it in the same way as other grammatical errors.

Self-paced reading has been used to study that.

A good example of this is a study by Wagers and colleagues (2008). This is a huge and complicated study with many

experiments; for this discussion, you only need to look at Experiment 2. Specifically, you only need to look at the experiment stimuli (in the top half of Table 3), and the experiment results (shown in

Figure 2); you don't need to look at anything else in the paper. What these results show is that people have a strong reaction to a grammar error (as shown by a big reading time slowdown in self-paced

reading) when there is not agreement attraction, but they don't slow down in reading (i.e., they don't immediately notice the error) when there is agreement attraction.

In the class discussion session, explain this concept and this finding to the class. Then, have students discuss and brainstorm why they think this happens—i.e., why exactly is the grammar error so

much harder to notice in "the musicians who the reviewer praise..." than in "the musician who the reviewer praise"?

(If you want to go even deeper, you can also discuss Experiment 3. Comparing the results of Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 shows another important feature of agreement attraction: there is a bigger effect

went the "attractor" is plural than when it is singular. In other words, the error in "the musicians who the reviewer praise" [Experiment 2] is not noticed at all in self-paced reading, whereas the error

in "the musician who the reviewers praises" [Experiment 3] is noticed a little bit. Both of these are grammatically wrong, and for the same reason, but one has a bigger impact on self-paced reading.

If you want, you and the rest of the class can try to brainstorm thy there is this asymmetry.)

In self-paced reading, effects (e.g., slowdowns in reading time) often happen one or two words later than where you would expect them to.

For one example, let's look at Experiment 1 of Omaki et al. (2015). This experiment examined sentences like the following:

- The city that the author wrote regularly about was named for an explorer.

- The city that the author who wrote regularly saw was named for an explorer.

These sentences are a bit complicated, but both are grammatical. (The second one has a subject relative clause in it).

In sentence #1, though, at the moment people read "wrote" they may be surprised, because at first they might interpret this as "The city that the author wrote...", i.e., that the author wrote a city. Of

course, a city is not something a person can "write". (We can write about a city, but we can't "write a city".) So, at the moment a person reads "wrote", they might be surprised, and they might

have a slowdown in self-paced reading.

On the other hand, in sentence #2, there should be no problem, because "wrote" is inside an island. "The city that the author who wrote..." would not be intepreted as saying the author wrote a city. (What

the sentence really means is that this author wrote regularly [about other things], and this author happened to see a city, and that city was named after an explorer.)

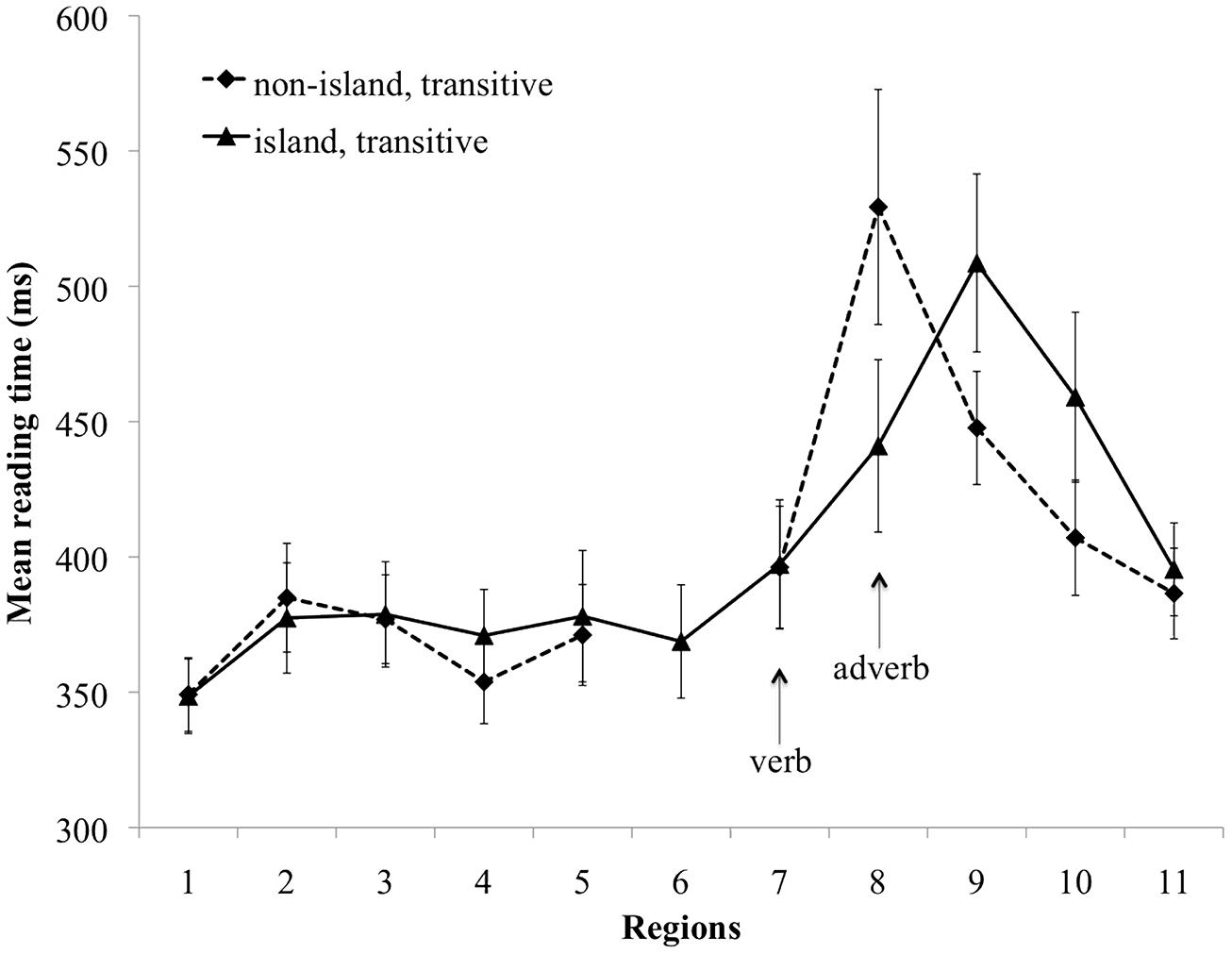

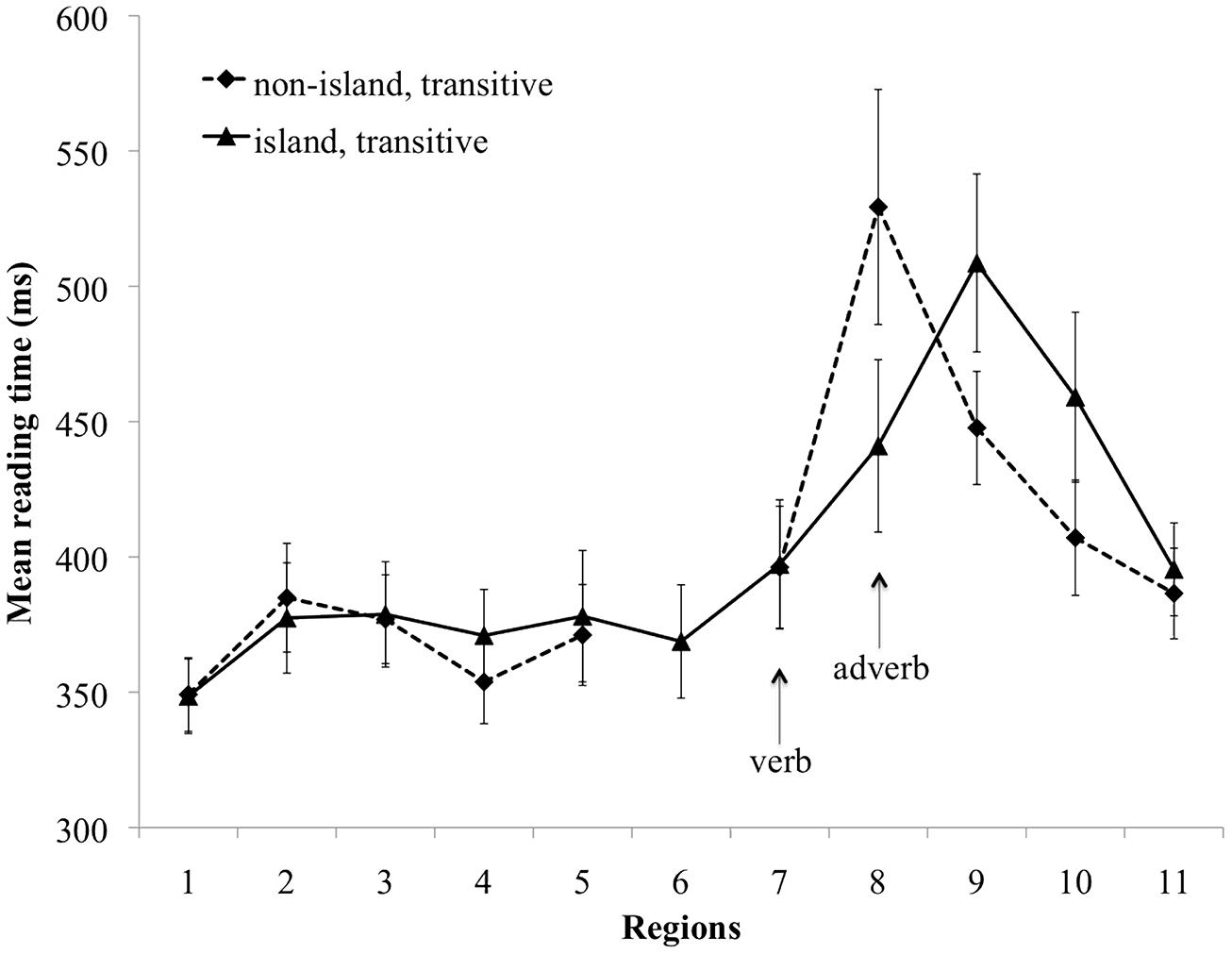

In the figure below we can see the self-paced reading results. Sentence #1 (which is called "non-island transitive" in this figure and is shown with a dashed line) is indeed read more slowly than sentence

#2 ("island transitive", solid line). But this slowdown doesn't happen at the verb, where we expected it; it instead happens one word later.

The Wagers experiment from the other discussion activity also has an example of the same thing: there is a reading slowdown, but it happens one word later than expected.

This is called a spillover effect.

In the class discussion session, introduce the concept of spillover effects to the class (you can use this example or another one), and then have them discuss and brainstorm the following two topics: Why

do spillover effects happen? And what consequences might they have for research (i.e., if we want to design a self-paced reading experiment, is there anything particular we should do because of what we

know about spillover effects?)

Read a paper that reports a self-paced reading experiment. During the class discussion session, briefly summarize the paper to the class (just enough so they can understand what it was about and what it

found; you don't need to talk about every detail) and then have them discuss it. Discussion could include critiquing it (e.g. talking about if there are any problems with the study, any alternative

explanations of the results, etc.), brainstorming similar kinds of research that could be done using a similar method, brainstorming ways that the implications of the results could be important in other

areas, etc.

The paper you choose could be anything, but it probably should be one that's not too complicated (some sentence processing experiments use extremely complex sentences or are about very subtle theoretical

topics and thus might not be easy to summarize and discuss in a short period). Off the top of my head, here are a few papers that include self-paced reading and that I think are not extremely

difficult:

- Fiorentino, R., Bost, J., Abel, A.D., and Zuccarelli, J. (2012). The recruitment of knowledge regarding plurality and compound formation during language comprehension. The Mental Lexicon, 7, 34-57.

- He, Xiao & Elsi Kaiser. (2009). Consequences of Variable Accessibility for Anaphor Resolution in Chinese. In S.L. Devi, A. Branco and R. Mitkov (eds). Proceedings of the 7th Discourse Anaphora and Anaphor Resolution Colloquium (DAARC 2009), pp.48-55. AU-KBK Research Centre, Anna University.

- Li, David Cheng-Huan & Elsi Kaiser. (2009). Overcoming Structural Preference: Effects of Context on the Interpretation of the Chinese Reflexive Ziji. In S.L. Devi, A. Branco and R. Mitkov (eds). Proceedings of the 7th Discourse Anaphora and Anaphor Resolution Colloquium (DAARC 2009), pp.64-72.

- Politzer-Ahles, Stephen, & Robert Fiorentino (2013). The realization of scalar inferences: context sensitivity without processing cost. PLoS ONE, 8, e63943.